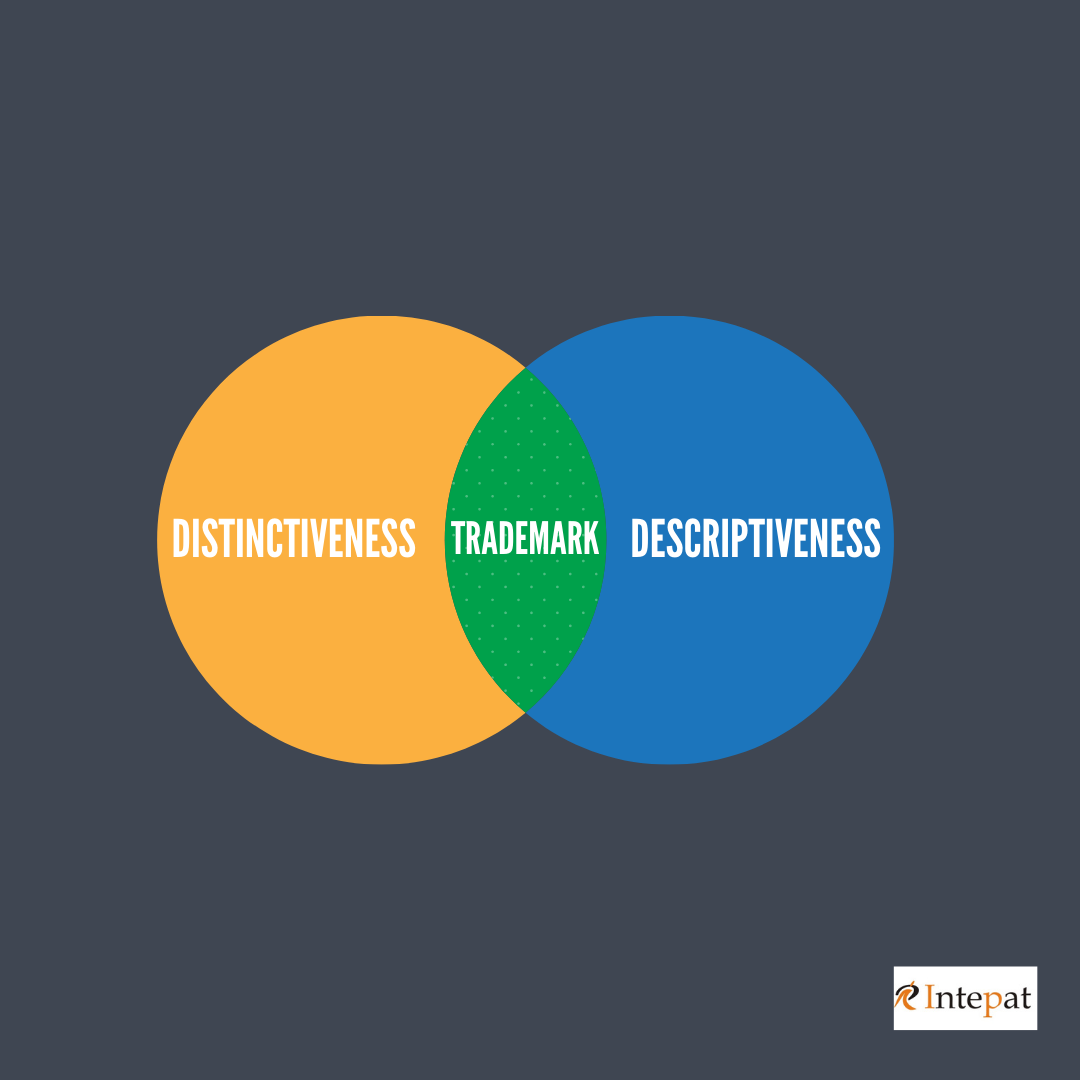

A successful trademark is a valuable asset that can boost the reputation of a brand and affect the preferences of its consumers. We opt for trademarks when we form a new, distinct meaning to the current word. Besides, we can also use it when we coin a new term to prevent customer confusion on the market and also to distinguish the origin of the products and services. Now, let us look into the difference between the distinctiveness and descriptiveness of the trademark.

Distinctiveness:

The Trade and Merchandise Marks Act 1958 states that a trademark that is not a distinctive mark is not registrable in Part A of the register. Distinctiveness means we should be able to differentiate a product from other products in the market. Furthermore, it should also ensure no such mark exists during the registration process.

However, we can also register a mark in Part B, even if it was not “distinctive” but “capable of distinguishing” between its owner’s and others’ goods.

In The Imperial Tobacco Co. of India Ltd. v. The Registrar of Trade Marks [AIR 1977 Cal. 413], the Calcutta High Court stated that distinctiveness means ‘some quality in the trademark which earmarks the goods so marked as distinct from those of other producers of such goods.’

Distinctiveness is the inherent capacity to differentiate between your products and services from those which provide the same goods and services. Hence, we cannot register the signs that identify the product or services to be distinguished.

For example, let us consider the mark ‘diet ice cream.’ The business offers products such as ice cream, cold drinks, shakes, etc. First, in this mark, the word ‘ice cream’ means the product itself, and ‘diet’ means it contains fewer calories. So, we cannot register it under the trademark act.

The 1999 Act incorporates Part A and Part B of the 1958 Act. We can register a trademark under the 1999 Act if its existence is distinctive, meaning it should be capable of distinguishing between the goods or services of one person and that of another.

In W.N. Sharpe Ld. v. Solomon Bros Ld. [(1915) RPC 15], it was held that certain words such as “good,” “best,” and “superfine” were incapable of adoption as they could not have a secondary meaning and were not capable of registration.

In Cluett Peabody & Co. Inc. v. Arrow Apparels [1998 (18) PTC 156 (Bom)], the court stated that the mark must be distinctive, and it must show the source of the goods to the customer. Words like “Best,” “Superior,” etc., were not distinctive of the goods, and they were only descriptive and hence incapable of constituting a trademark.

Trademark distinctiveness is an essential concept of the law applicable to trademarks and service marks. Therefore, we can consider a mark “distinctive” because of its ability to “identify and differentiate” goods or services.

The spectrum of distinctiveness

Registering trademarks without distinctive characters are complex, and the United States’ protection depends upon this spectrum.

1. Generic Marks: We use the term generic marks to designate a class or category of product or service. In M/s. Three-N-Products Pvt. Ltd. v. M/s Kairali Exports and Anr., Delhi Court ruled that “a generic mark requires a greater degree of proof and burden of proof on one who claims the distinctiveness is much higher.”

2. Descriptive Marks: These trademarks only describe the goods or services we use.

3. Suggestive Marks: Suggestive mark enables the consumer to exercise his imagination or perception about the goods, T.V Venogopal Vs. ushodaya Enterprises Ltd. &Anr 2011

4. Arbitrary Marks: These marks have a specific meaning, but they have no connection to the goods or services of the business.

5. Fanciful Marks: Businesses often come up with fanciful trademarks to represent their products or services, and these marks have no other significance.

Let us look into some instances where we have protected the distinctiveness of the trademarks:

Laxmikant V. Patel v. Chetanbhat Shah and Anr.[AIR 2002 SC 275], The plaintiff was a continuous user of the trademark “Mukta Jeewan Colour Lab.” Finally, the other party was injuncted from using a similar mark. The court stated, “By virtue of its prior, continuous and comprehensive use, the word combination has acquired distinctiveness and is therefore protected.”

M/S P.K. Overseas Pvt. Ltd. v. M/S KRBL Ltd [2014 (57) PTC 129 (IPAB)], The Board acknowledged that the mark “Bemisal” had gained distinctiveness as a result of its continuous usage and prominent sales figures. Hence, it is a valid trademark. Therefore, this case portrays that we can use the sales figures to establish the reputation and goodwill of the trademark.

Descriptiveness

Most trademark controversies are on whether the trademark is specifically descriptive of products or services. Furthermore, we usually do not register descriptive words as trademarks; a trademark is descriptive if it transmits information directly.

In Consim Info Pvt. Ltd. v. Google India Pvt. Ltd. [2013 (54) PTC 578 (Mad) (D.B.) p. 606], the court stated that a “descriptive mark was a word, picture, or another symbol that directly describes something about the goods or services in connection with which it was used as a mark. Such a term may be descriptive of the desirable characteristics of the goods”. In short, descriptiveness in a mark directly describes the product or services to which we apply the mark.

To register a descriptive trademark, the owner must also persuade the Examiner that the applied trademark has gained secondary meaning and is subject to protection under Section 32 of the Act.

We are often left with the question of how to prove that any mark has gained distinctiveness or secondary significance. Hence, to justify the use of the mark, the proprietor of the mark must submit invoices, advertisements, and other related promotions.

There are three types of evidence that we can use to show secondary meaning:

– claims of ownership of similar trademarks with similar goods or services that were registered already,

– Five years of continuous use and actual evidence.

– In the case of Godfrey Philips India Limited v Girnar Food & Beverages (P) Ltd, [(2005) 123 Comp Cas 334 (S.C.)], the Supreme court held that “a descriptive trademark may be entitled to protection if it has assumed secondary meaning which identifies it with a particular product or as being from a particular source.” Sometimes, we can also trademark common words of a language or descriptive words when they have gained distinctiveness or secondary significance.

Determining mark descriptiveness

One should consider the following factors while determining the descriptiveness of a mark:

Dictionary meaning is one of the considerations when deciding if a trademark is descriptive. Nevertheless, the lack of definition is impossible if it is proved that the word has an understood and accepted meaning.

The first user of the mark – If the applicant is the sole user of any trademark, it does not justify the trademark registration if he uses it descriptively.

Intended user – We can consider a trademark descriptive if it describes the category of people who use the products or services.

Thus, when deciding to use a mark for specific goods or services, we should see that it has acquired a distinctive character even though the mark looks merely descriptive. Clearly, to avail protection for a trademark, it should be distinct and have a secondary meaning. We can calculate the degree of distinctiveness or descriptiveness based on particular products or services, and you can always get in touch with experts to register your mark.