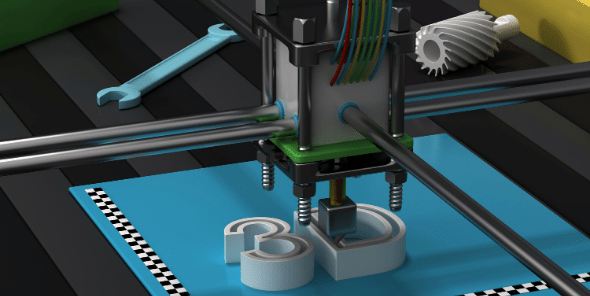

The invention of Gutenberg’s printing press has been hailed as one of the most critical inventions in humankind’s history. It allowed knowledge to be shared more cheaply and faster than before. Nearly 600 years later, technology today allows us to print from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) objects. This is due to the invention of 3D printing technology. Also known as additive manufacturing, 3D printing is the creation of solid objects from a digital file. The invention of this modern technology has created an array of opportunities and brings many challenges. In this article, we shall see how the regime of intellectual property rights comes into play regarding 3D printing technology.

3D printing involves using a digital file with the blueprint of the object to be created. These files are Computer-Aided Design (CAD) files and provide information to a 3D printer on the type of object to be made. 3D printing is called an additive manufacturing process, as the product is created by laying down successive layers of material to form the object’s final shape.

Surprisingly, the technology of 3D printing has been around for quite some time. The earliest version of this technology dates back to 1971 when Johannes F Gottwald patented an invention for an inkjet printer which formed removable metal fabrications on a surface. However, his invention was not commercialized, and it was not until 1984 that additive manufacturing techniques and equipment resembling modern 3D technology were developed. The need to adopt 3D technology in various sectors was seen in the 2010s when industrial material came to be created through this technology. Thus, within the past decade, we have seen the growth of 3D technology as a sustainable method of manufacturing.

3D technology has proved highly useful in several industries, and several products have arisen through its use. For example, 3D printing has been used to create mass-customized orthodontic aligners, carbon fibre frame eBikes, wearable textiles, low-cost surgical implants, prosthetics, and even a permanent residential house which was built in Yaroslavl, Russia in 2017 and which was completed 8-12 times faster than a typical house.

Protection Under Intellectual Property Law

One of the most significant advantages of 3D printing is the speed with which a complex shape or object can be created. Things which required capital machinery and a considerable amount of time to be reproduced on a scale can now be made much faster through this technology. Further, 3D printing also enables individuals and companies to manufacture certain things in-house, cutting costs on importing such material.

However, creating an object makes it easy for others to copy and recreate the same. Today, this issue becomes of utmost importance as the unauthorized creation of such an object amounts to an infringement of one’s intellectual property (IP) rights. Copyright, patents, designs, and trademarks are the category of IP rights most affected by the technology of 3D printing.

Copyright:

Simply stated, copyright is an exclusive right which allows one to prohibit others from reproducing their original literary, artistic, or dramatic work. To enforce the right, it is required that the work be expressed in some tangible form. 3D printing involves the physical creation of an object. Should the object possess an aesthetic value, it can be protected under copyright as an artistic or sculptural work. Any reproduction of such an original creation would then lay forward action for copyright infringement.

In the world of 3D printing, no object can be printed without computer software obtaining information on how to reproduce such an object. As explained above, this information is found in the form of a CAD file for 3D printing. A CAD file essentially consists of a code of instructions for the 3D printing software to understand and process the creation of the object based on such code. Modern IP regimes allow for the protection of software codes in the form of copyright.

In India, for example, the Indian Copyright Act of 1957 allows for the protection of the original literary works of an author. Under the ‘literary work’ category, Section 2(o) of the 1955 Act includes computer programmes. Thus, software code can be protected as copyright under Section 13 of the Act, which states that copyright subsists in an original literary work.

In the United States, copyright protection is granted to a computer programme when expressed in a tangible form. Software codes are this tangible form of expression of computer software. This ensures that the CAD files, which instruct a 3D printing machine on printing a particular object, can be copyrightable. Additionally, suppose the CAD file contains information for creating an existing product. In that case, it may be considered a derivative of the original work and hence still protected under copyright.

Moreover, the CAD file is also an original intellectual effort of the creator. Thus, one can claim an infringement of rights against any unauthorized person who uses the file for commercial use. Yet, any person using the file for personal use, not for profit, does not infringe upon the author’s copyright as he would be protected under the doctrine of fair use, which permits such limited use without the need for obtaining permission from the original author of the work.

An interesting case study arises relating to copyright in a 3D printed object. Ulrich Schwanitz, a designer, created a 3D printed design called a ‘Penrose triangle, an optical illusion. He uploaded the CAD file of the same on a website called Shapeways and allowed people to buy a copy without telling them how he created the object. However, another designer successfully recreated the 3D printed design and uploaded the corresponding file on a free-to-share website dedicated to 3D printing called Thingiverse. This allowed the public to download the file and create the design for themselves freely. While Thingiverse took down the file after notice from Schwanitz, the question of Schwanitz’s copyright in the file remains unanswered. However, as noted by one commentator, Schwanitz’s claim for copyright infringement would not stand as the object for which it was claimed to be an optical illusion. US law does not allow for the protection of optical illusions as copyright.

A point to be noted here is that objects which are pure of a helpful nature and not of an aesthetic nature cannot be protected under copyright. Thus, 3D printing a screw or pole cannot be claimed to be an infringement of copyright if it is devoid of any aesthetic value and is merely of a technical nature. However, such objects which lack aesthetics but have technical use can be protected under patent law.

Until the next post for part II of this article, we shall discuss the applicability of other IP laws on 3D printing technology and the challenges created by using this technology on those laws.