I: Understanding Plain Packaging:

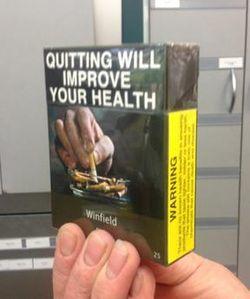

The recent WTO ruling upholding Australia’s right to standardize packaging of tobacco products has not only struck fear in the hearts of tobacco companies but has also forayed into plain packaging laws and, the role they play in balancing intellectual property rights and public interest and safety. Simply put, the act of displacing distinctive and appealing packing of tobacco products with homogenous design dominated mostly by pictorial and textual warnings related to the ill-effects of tobacco consumption, is called plain packaging. Countries such as Ireland and the UK have also made headway in consciously limiting the exercising of intellectual property rights of the proprietors of ‘disfavoured’ products. Imputing the lessons from such progressive perspectives into the Indian paradigm will be difficult, but not impossible as the judicial and legislative back and forth in India has offered substantial clarification.

II: The Development of Tobacco Legislation:

India has over 100 million tobacco users with almost one in three adults admitting to having used it regularly. In an effort to curb the tobacco epidemic, the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 (“COTPA”) and the Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Rules, 2008 were introduced. However, the fundamental regulatory purpose of the legislation was being vitiated through the sale of tobacco products in attractive packaging. It was also directed by the Supreme Court, having received no response till date, to the Ministry of Health, pursuant to a PIL being filed in 2016, that delaying the implementation of plain packaging was in violation of the rights of the citizens under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution.

Conversely, with a noticeable decrease in tobacco consumption of 3 percent in Australia post the introduction of plain packaging laws in 2011, and with Brazil finding success by removing descriptors from the plain packs that further decreased the ratings of appeal, taste and smoothness, and associations with positive attributes, certain changes were required to be made to reassert the importance of health over commerce in India.

To that end, Article 3(1)(b) of the above Rules was altered in 2014 to increase the size of the health warning on the principle display area from 40% to 85%, along with printing of manufacture details and the prohibition of brand promotion. After all, Article 47 of the Constitution vested a duty with the state to raise the level of nutrition and standard of living to improve public health.

III: Role of the Judiciary: Constitutional Considerations

The amendment was challenged in the Karnataka High Court in 2017 as being violative of Section 28 of Trade Marks Act, 1999, Article 14 and Article 19(1)(g) which refers to exclusive right of trademarks, right to equality and right to business, respectively. Since the State could not establish the inadequacy of the previous 40% requirement with empirical data, the reason for uniform applicability for all tobacco products having different packaging schemes and the requisite balance between a proprietor’s trademark rights and public health concerns, it was held to have a detrimental, unjustified impact on business in a discriminatory manner that caused unfair limitation of intellectual property rights, and consequently struck down. Moreover, Article 11 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) also recommended the introduction of warning labels for 50% of the packet cover, so it seemed prima facie that there was no meaningful objective that was being accomplished.

However, in Health For Millions Trust vs Union Of India, the Supreme Court stayed the High Court’s order and reinstated the 85% requirement as it not only viewed that as a reasonable restriction on Article 19(1)(g) but also that a policy based decision on the health risks posed to citizens could not be struck down, simply for the want of empirical data. Instead of hinging on the rationale behind the numerical increase, it subscribed to the view that any display warning below 85% did not adequately inform and safeguard the health of the consumers. Business and Intellectual Property considerations fell flat when there existed a need to prevent the desensitisation of products causing the “destruction of health”. The Trademark argument was also handled internationally with the UK arguing that as a negative right, limitation of the trademark did not withhold the rights of the proprietor and, Australia debunked the claim that it was seizing the intellectual property of tobacco companies by pointing out that there was an proprietary benefit to the Commonwealth that would amount to an acquisition.

IV: Problems with Plain Packaging

India took a step in the right direction by intervening on behalf of Australia in the WTO dispute. However, cost-effective tobacco control mechanisms aren’t free of concerns as it makes it harder to control the entry of counterfeit products, strengthening the possibility of plain packaging doom for other disfavoured industries such as soda and alcohol, limits the ability to exercise copyright and trademark rights for tobacco companies to just on paper, increases the attractiveness of tobacco consumption that stems from the appeal often associated with experimenting with the illicit and the forbidden, might usher in a brutal price war as a distinguishable factor to increase consumption and, almost 75% of all cigarettes in India are sold loosely, thus minimizing interaction with the homogenous packing. Over 14% of all consumed tobacco was illegal in 2013 in Australia, highlighting the potential for adverse consequences.

V: Conclusion

While it is hard to truly gauge at the effectiveness of policies on behalf of public health, it is an established fact that tobacco consumption increases the incidence of various forms of cancer. Intellectual Property and Commerce can only be afforded protection when the health of the individuals participating in such spheres have been assured. However, the pros and cons must be analysed and an enlightened collaborative approach must be taken by the branches of the government to ensure maximum positive impact to the parties involved from standardized packaging.